Jarrett Adams, born and raised on the Southside of Chicago, graduated high school in 1998 at the age of 17.

One night that summer, Adams snuck out with two friends to go to a party at the University of Wisconsin-Whitewater.

Three weeks after the party, Adams found a business card from a police officer in his front door. A girl at the party had accused him and his two friends of rape. Despite a witness statement that contradicted the accuser’s story, Adams and his friends were arrested and charged with sexual assault.

“We were totally innocent. That was an absolute and total lie,” Adams said. “I realized very quickly early on it had nothing to do with the truth, it was about race.

It was about who was accusing me and how the accused looked. We were all Black and we were accused by a White girl of rape, so no matter what we said we were never going to be believed. Never.”

“They give you an opportunity to address the court,” he remembers. “When I got up, I told the court, ‘Look, I want to apologize to my parents, I’m even going to apologize to the parents of my accuser. But I’m not going to apologize for a rape that never happened.’ The judge found that I wasn’t being remorseful and she gave me an additional eight years in prison.”

“I was absolutely terrified,” he said. “I was one of the youngest faces in that maximum-security prison, about 140 pounds … And I’m around a bunch of grown men. It was an out-of-body experience from the time they said ‘guilty.'”

After being imprisoned for a year and a half, Adams had a conversation that changed his entire approach.

“I had a cellmate who was an older white dude who was in prison for two life sentences … he said, ‘Look, you get up every day and you get out here and you play chess, you play basketball and you don’t act like you’re innocent.

Innocent people, they’re in the law library,'” Adams said. “Ever since that day, that was like a wake-up call to me and I started to try to grasp the law.”

While in prison, Adam looked through newspapers to identify attorneys litigating cases in the state of Wisconsin. If it was a case that could support his argument, he would write a letter to the attorney, hoping for a response.

In 2004, the Innocence Project agreed to take on Adams’ case, and in 2006, eight years after the arrest, they argued his case to the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals in Chicago.

The court unanimously overturned Adams’ conviction, on the grounds of ineffective assistance of counsel. In February 2007, after he had been incarcerated for nearly ten years, he headed back into a Wisconsin courtroom for the state to dismiss all charges against him.

“In less than 10 minutes, the motion was filed, the judge threw down her gavel and I was gone and released out of the courtroom,” Adams said. “That judge never looked me in my eyes at all. When I walked out of that courtroom, I said, ‘You might not look at me now, but you’re going to have to see me for the rest of your life.'”

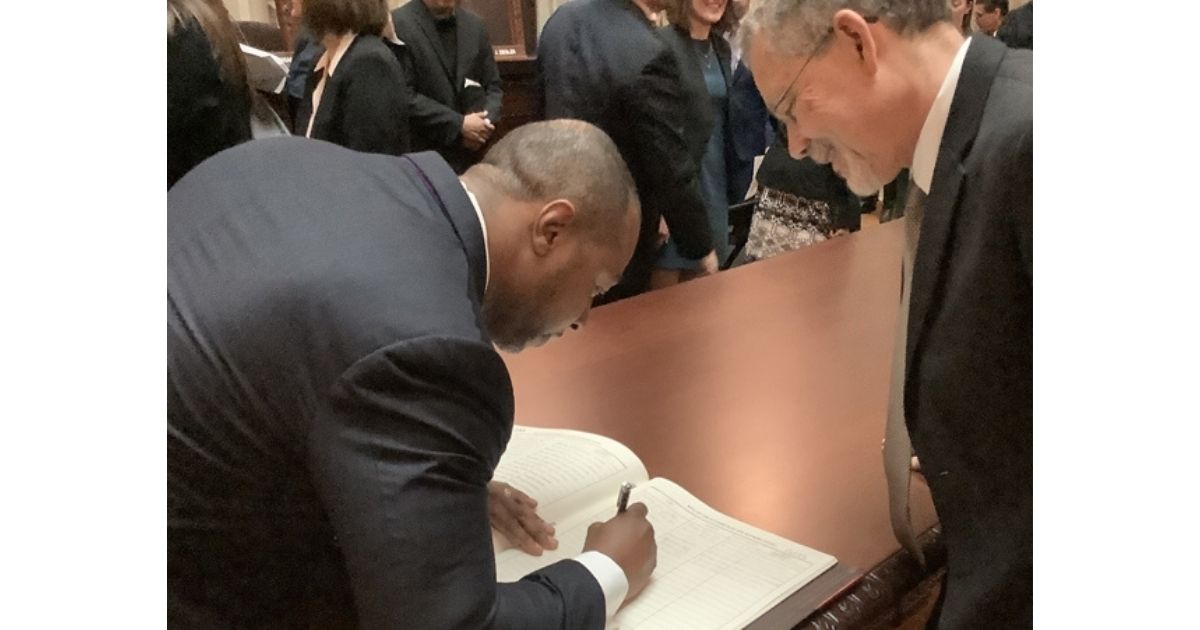

Adams was released in February 2007, and in May of the same year, he was enrolled in college. In May 2015, Adams graduated from Loyola University Chicago School of Law.

“I strongly believe that the problems with our criminal justice system will only get better when we infiltrate the system, meaning more Black judges, more Black prosecutors, more Black, young Black attorneys, like young Black knowledgeable, powerful young men changing the stereotype that we’ve had to deal with forever,” Adams said. “That’s what we need, and I’m hoping my story will go to that movement.”